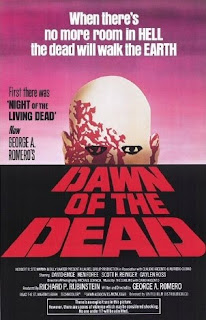

As you will soon find out from reading my mass communications class essay; Dawn of the Dead is serious business.

Dawn of the Dead is a horror film from 1979. It was originally released in 1978 to great success in Europe, but in a different cut than director George A. Romero’s original version. This was due to an MPAA battle that raged over the more controversial aspects of the movie. The MPAA is the ratings board for American film. They wanted to brand the movie with an X-rating due to it’s over the top extreme violence and (on speculation) it’s social satirical content that took on the values of consumerist America. Dawn of the Dead is a zombie film. In it the zombies are explicitly representing the consumer culture that was budding during the time of its release. The majority of the picture takes place in a brand new shopping center, where survivors of the zombie apocalypse take refuge. Long montage sequences of the walking dead strolling mindlessly through the various shops and facilities at a local shopping mall shake the viewer’s perspective on consumerism and the capitalist mechanizations that keep it fueled. Leaving one with its nihilistic brand burned into their brain.

But let’s back track to the beginning of the narrative. At the start of the film we are introduced to the female lead, Fran, who wakes from a nightmare into the chaos of a television station in crisis. The dead are rising up and eating people, and everyone is turning to local media outlets for information on what to do. In the films first of many dark turns, the head broadcaster insists on constantly displaying the rescue stations over the programming, even though they have all been overtaken by zombies. The man is so in tune with his job and its quest for ratings that he does not care if he is sending people to their death, as long as they don’t change the channel. Fran takes the list off the air, and is met with resistance from her boss. The film is siding with the libertarian idea of emphasis on the individual. She took matters into her own hands, and further does this later in the film when she abandons her job to get into a helicopter with her boyfriend and look for another place to wait out the catastrophe. Her defiance is portrayed as admirable, and she is rewarded for it when she survives longer than all but one other character in the film.

The other two main characters are introduced at a raid on a housing project where zombies are being kept alive by their fearful and confused relatives. Mistrusting government and its agencies has never been more justified than in the sequence that follows. A crazed SWAT member goes on a rampage shooting every person he sees while going on a racist rant. The two level headed members of the team subdue the maniac, and soon decide to abandon their posts as well and take off with the couple in their helicopter.

While the group is on the trip that ends at the mall, they encounter some rural redneck zombie hunters. The atmosphere is that of a carnival event, like a tail gate party to battle the living dead. People are drinking beer, and bragging about how many zombies they have shot in the head. This lines up well with the cynical Mass Society theory, holding that as long as you paint the apocalypse in a favorable light (and give people beer) the dumb audience will stay entertained.

Arriving at the mall, Steve (the helicopter pilot, and Fran’s boyfriend) reflects on the hoard of zombies gathering in and around the shopping center. “This was an important place in their lives,” he says. A message can’t be more explicitly delivered than that. So hilariously cynical that it is often met with laughter from an audience. As time passes inside the mall, we see the characters begin to adjust to life after the zombies. They roam the mall, using up their endless free time with arcade games and an ice skating rink. At night they dine in and play high stakes poker games with 50 dollar bills stolen from the bank below them. But as time passes something starts to change. The characters become unhappy, bored with their meaningless shuffling about inside of the mall. They are slowly realizing what the viewers have already been beaten over the head with. The consumption of goods in a protected environment is a life without meaning. The characters trying to survive and keep the zombies out are turning into them themselves through their total immersion in the consumer lifestyle. That a script filled with such a dark and nihilistic message would end up performing so well is telling of the social situation within post-Vietnam America. The public was enraged and invigorated when the films predecessor, Night of the Living Dead, came out in 1968, but now in 1979 they are sick of caring, and want to go to the mall. Here Romero slaps them across the face, telling them to wake up to the grim reality waiting for them at the end of that road. No matter how many trips to the mall you make, you’re just dulling yourself down into another flesh eating cadaver.

Audiences across America and Europe received the film with open arms. It grossed 55 million dollars in the United States alone, which was unheard of for a film like this at the time especially since it was released unrated (something now only reserved for DVD releases). The message of a consumerist society gone mad, with no help to be had from religion or science struck a chord with people across the world. Amazing considering how ahead of it’s time the message would turn out to be (with the dawn of the 80’s me-generation and shallow ideal of financial gain about to have a death grip on Reagan era America). It’s a theme that is revisited in other horror films like American Psycho and the remake of Dawn of the Dead that was released in 2004. The context of the film is important, since it lay on the cusp of one of the most excessively culturally vapid decades in history. It’s ironic that social commentary of this high caliber would come in the form of a zombie movie, but there really is no more scathing metaphor for a generation’s complacency and misguided values.

No comments:

Post a Comment